Interviews

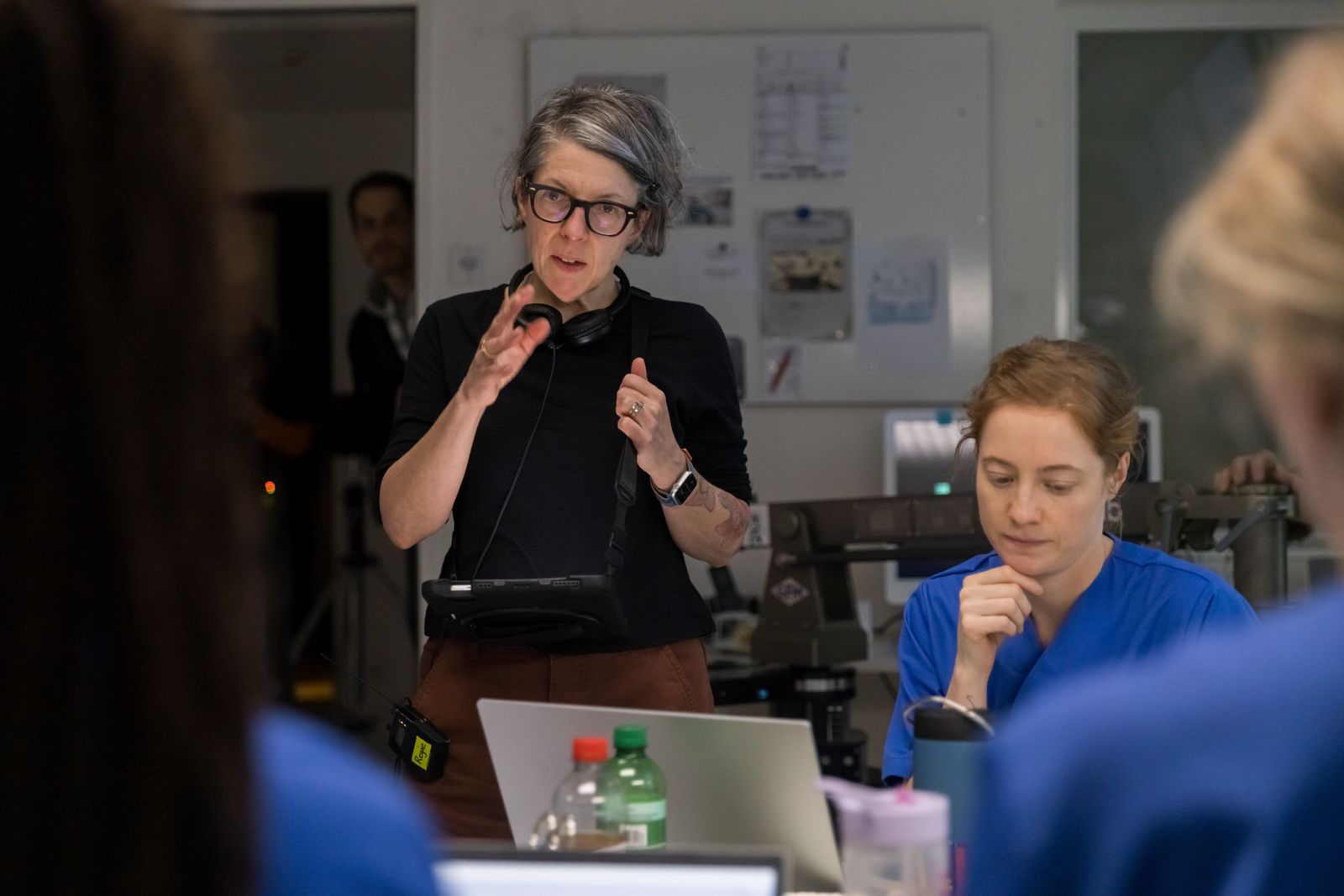

Interview With Director Petra Volpe (Late Shift)

Since premiering at Berlin Film Festival in February, Late Shift has proved to be a huge success. Focusing on a nurse’s overnight shift at a hospital in Switzerland, it feels incredibly timely and with a message that will resonate globally.

We had the pleasure of speaking with Petra about the film, her collaboration with star Leonie Benesch, who occupies almost every frame. She also discussed her research and the involvement of real-life nurses and what she hopes the film will achieve in terms of conversations.

When did you first get interested in this topic and decide you wanted to make a film of it?

It was many years ago, before COVID, because I lived with a nurse for many years, and I just observed how her working conditions deteriorated year by year, and also the huge personal toll it took on her not having time for her patients. So it’s been on my mind for many years, but I didn’t quite find the form for it until I read a book by Madeline Calvelage, where she just describes one shift. It read to me like a thriller. I remember I got heart palpitations, and I thought that’s the kind of movie I want to make. I want to create a movie that’s a physical experience, more than a movie, which puts you in the shoes of a nurse just working a relatively normal shift. From there, I did a lot of research. Madeleine, the writer of the book, was one of my consultants, but I also had a Swiss nurse who consulted me, and then I did tons of interviews with nurses. I went to the hospital myself to observe, to speak with the people, to get a broad idea and perspective on the job and what it means to do this work every day.

Were there any films or other media that you took inspiration from?

I think it was more like what we didn’t want to do. I think the inspiration, or what was really, our guiding light was trying to stay really true to the drama of a normal shift, the drama of the very everyday situation when one person is missing on a ward, like, if it’s just one, if there’s not enough nurses, you can’t be in two places at the same time, and what that means for the nurse, but also for the patients. So, it was more like the everyday. How can we capture the emotional and physical reality of this work in the most precise way?

We decided quite early on to stay very strictly in the perspective of the nurse. Of course, there we had some examples, like films by Christian Mungu, for example, like to really strictly tell the story from the perspective of the nurse, and not also delve into the stories of the patients, because, she goes into a room, she must grasp the reality of a patient within a few minutes and leave again. We wanted to recreate that and what that emotionally means for a nurse to do that every day. Even if you want to stay longer with the gentleman with the dog, you don’t have the time to do that. The toll it takes on somebody when you must experience that every day.

It’s based entirely around the one character. Did you speak to Leonie a lot about prep, with so much emphasis on her performance?

Yes. I mean, I needed an actress who really has a very physical and visceral and physical intelligence, almost like a dancer, because it was clear she has to learn all these nurses, the gesture and the kind of the way, the way the nurse carries herself, the way she speaks, she has to grasp it in a in a really short time. So, I needed somebody who was very natural and had a natural talent to learn these things quickly. Leonie has that very much, and she had a coach. We saw the character really, like an athlete, and that’s how we saw the nurses when she also went to the hospital to observe them.

For me, what they do is like physical and mental athleticism, you know, and we wanted to capture that. So, she had a coach who almost trained her like an athlete to do all these things quickly. Leonie took the syringes and the IVs home to learn how to put them together and practice it repeatedly until it looked like she’s been doing this for 20 years. Nadia, our nurse consultant she was by our side during the whole shoot. She was coaching Leonie, and she was helping me. She sat next to me, next to the monitor, every take, so we didn’t make any kind of technical mistakes. Because if you put the job at the centre of the narrative, you cannot make mistakes. If you want to celebrate, the nurses work and you make a movie for them, they’re an extremely strict audience. If you make mistakes, they won’t forgive you. So, we wanted to be mindful of that.

You’ve had a lot of success with the film premiering at Berlin and SXSW London. You must be delighted with the reception and the awareness that the festivals have given the film?

What’s, the most touching thing for me is that I’ve never gotten so many letters from nurses or audiences like after a movie, I get so many letters by nurses who wrote to me thank you for this movie, because for the first time, I feel seen, and I think this means a lot to me, and I always forward it my team.

It’s really very important for us to make a movie that celebrates nurses and their work and to get their feedback and get these letters where they say, I’ve had a shift just like that today and thanking us for making this movie and putting this work on the big screen and celebrating it in all its complexity, that really means a lot to me, and also I know to Leonie and my DP, my editor, we are always very honoured to get these letters.

I think it’s great that the movie is a big commercial success, because it shows people are, you know, she’s a different kind of hero. She’s an everyday hero and people are interested in seeing these kinds of movies that are tackling a social issue in a, you know, captivating way and and it can put people into cinemas. That for me also makes us hopeful for cinema.

The film is set in Switzerland, but there’s a very international feel to it, because obviously, this is an issue that many will relate to. You spoke to US nurses and US hospitals as well. Can you talk us through that?

I think it’s a very universal topic. There’s a shortage of nurses globally. You see it in the numbers. In the end of the movie, The WHO has a really devastating estimate of how many nurses are missing. It’s a huge global crisis, and it’s not treated as such. It’s very symptomatic because it’s a woman’s job. 80% of people who do this job are women. They’ve been trying to fix this for many, many years. During COVID, everybody had a higher awareness of the importance of this work, and after that, it disappeared again. Politicians don’t treat this topic as a very urgent topic in society, because it’s also very symptomatic that everybody feels women can be pushed to the brink, you know. It’s a job where you can have a lot of emotional blackmail because if they go on strike, the patients will die.

So, you can kind of count on the women that they won’t do that, and it’s being taken advantage of, you know, of the goodwill and the professionalism of the women who do this job. I think eventually, like all of us, we are all potential patients, and everybody will need a nurse sooner or later. So, them being treated well is in our best interest. Is in my best interest that I have a good nurse and that she works under the best possible conditions, you know. It’s not primarily in their interest. It’s in my interest, you know. So, I really hope that the movie can raise some awareness, and at least in Switzerland and Germany, it was able to stir up some political discussions. A lot of hospitals showed the movie to their staff. The union used the movie for awareness. The schools are going with their students. I don’t think the movie can change the world, but I think it can, you know, put a spotlight on something important.

The interactions in the film are those real interactions that you’d heard about from nurses. There’s a sense of realism to them.

Yes. I mean, it’s very much inspired by reality and our observations. The patients are inspired by research, but also by my personal stories. I have a dog, for example, and the gentleman with the dog is very much inspired by my own fear and research, like the doctor told us that his patients very often worry about their pets the most. That’s also what nurses told us. For example, people who have pets heal quicker because they want to get home to their pet. Also, people who are very severely ill, their biggest worry is usually not even themselves, but what happens to their pet. I think there’s no lonelier place than a hospital at night or a hospital bed. Susan Sontag says, when you become ill, you become a citizen of a foreign country. I think that’s a very true sentence. I think a nurse is the one person who can help you with your solitude a little bit, and we need to be aware of that.

Are you able to tell us what you’re working on next?

I just shot a movie in the UK. In Shrewsbury, and the film takes place in an American men’s prison, but we shot it in the UK, and it’s almost all men. It’s not a female-driven movie, it’s about Alzheimer’s and dementia in a man’s prison.

Is there anything else you wanted to highlight about Late Shift?

I think what’s interesting from a movie making perspective interesting is the camera work and the editing. We really wanted to create a movie that feels like a physical experience, and that’s such a collective effort of all the departments. My DP and I thought about it very much, how to visually make the hospital an attractive place, but also how to capture the work of the nurse and her rhythm and flow, and that continued in editing and with the music. All the heads of department, also production design, we all tried to honour, this work, and try, to think, how can we put people into the shoes of a nurse? How can we create this effect that people who watch the movie feel like they’ve done the shift that was our aim. We wanted people to feel exhausted after the movie so and that entails every department had to do their work to achieve this effect.

Late Shift is in UK cinemas on Friday 1 August

-

Featured Review4 weeks ago

Featured Review4 weeks agoLondon Film Festival 2025 – Hedda ★★★★

-

Featured Review1 week ago

Featured Review1 week agoPredator: Badlands ★★★★

-

Interviews4 weeks ago

Interviews4 weeks agoDon Worley on Second Chances, Making Movies and Stand-Up Stages

-

Featured Review4 weeks ago

Featured Review4 weeks agoLondon Film Festival 2025 – High Wire ★★★★

-

Featured Review4 weeks ago

Featured Review4 weeks agoLondon Film Festival 2025 – Frankenstein ★★★★★

-

Movie Reviews3 weeks ago

Movie Reviews3 weeks agoLondon Film Festival 2025 – Left-Handed Girl ★★★★

-

Featured Review3 weeks ago

Featured Review3 weeks agoLondon Film Festival 2025 – Die My Love ★★★★

-

Movie Reviews3 weeks ago

Movie Reviews3 weeks agoLondon Film Festival 2025 – The Chronology Of Water ★★★